A Wedding Homily

Wedding homily by Pastor Ryan Biese in August 2015 Read More

Welcome to Ulster Worldly, a blog about the history of Presbyterianism. Many of these stories come from my own family, many others come from my own denomination.

Tim Hopper

Raleigh, NC

Wedding homily by Pastor Ryan Biese in August 2015 Read More

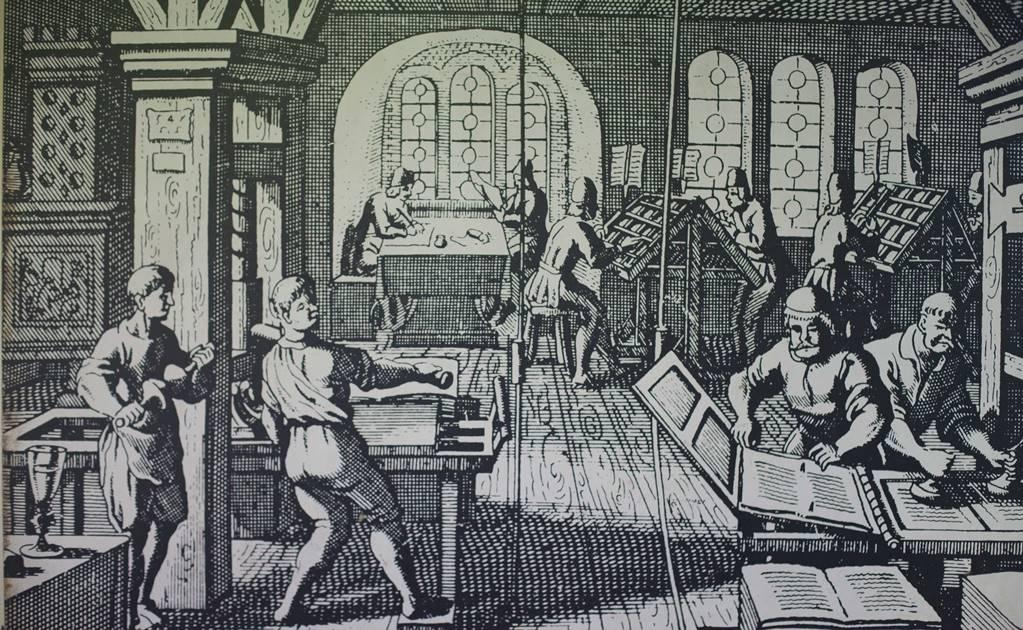

Examination of how influential Christian leaders like Martin Luther, Abraham Kuyper, J. Gresham Machen, and R.C. Sproul effectively used emerging media technologies of their times to spread their theological messages and the gospel Read More

I have served as a deacon in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) since 2014. On the Hopper side, I’m a 5th generation Presbyterian officer. Here are my ancestors who served as officers.

My father, David Hopper, is a ruling elder in the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). He was previously a ruling elder in the Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC).

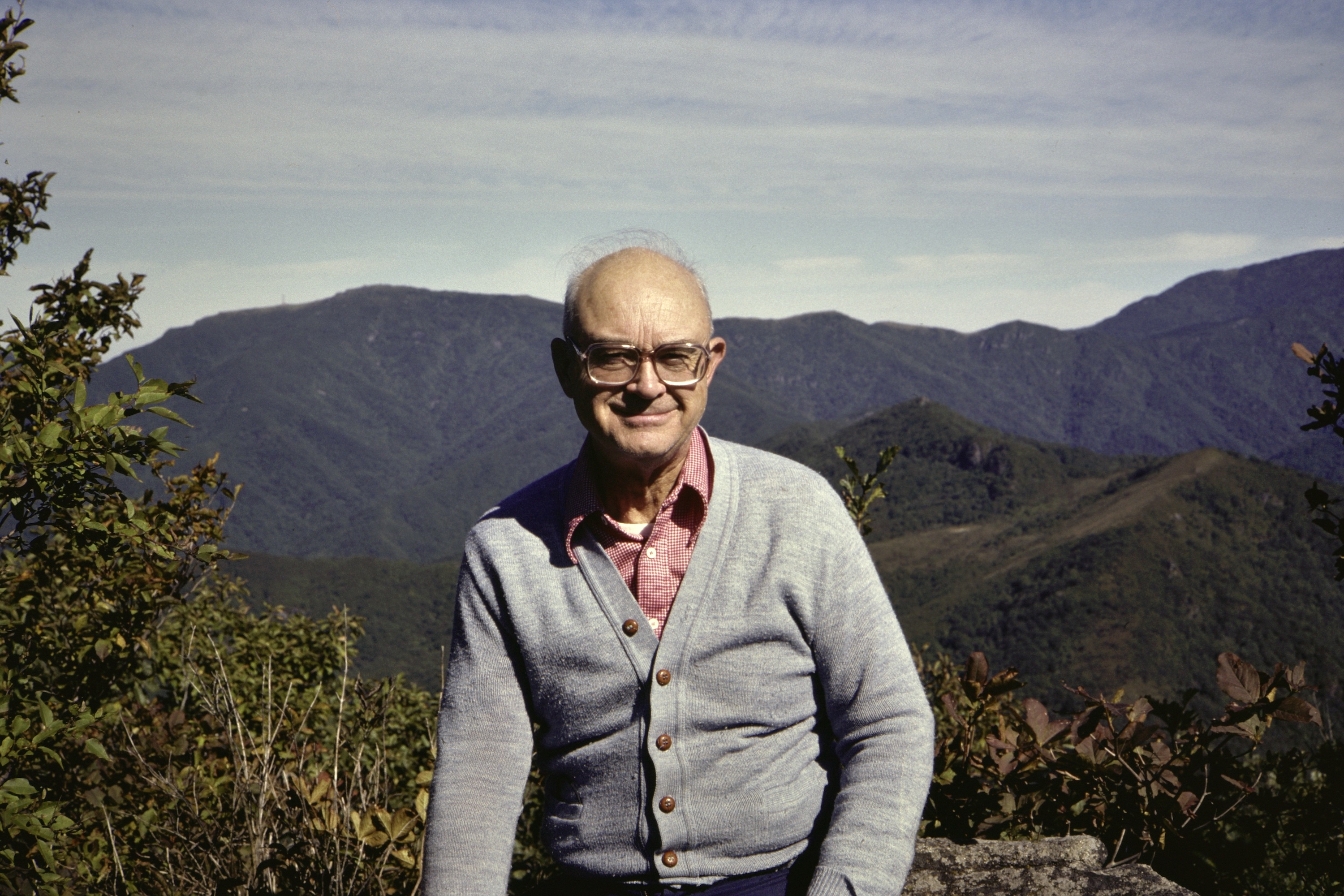

My grandfather Joe Barron Hopper (1921–1992) was ordained by the Montgomery Presbytery of the PCUS in 1945. He served as a PCUS (and later PCUSA) missionary to Korea for 38 years.

Joseph Hopper (1892–1971), father of Joe Barron, was ordained by the West Lexington Presbytery (PCUS) in 1917. He served as a missionary to Korea.

Hershey Longenecker (1889-1978) was ordained by the Presbytery of Transylvania (PCUS) in 1916. Hershey was a first-generation Presbyterian (coming from an anabaptist family), as was his wife (coming from a Methodist family). He served as a missionary in the Congo.

George Dunlap Hopper (1848–1913), a farmer and businessman, served as a deacon for 11 years and then a ruling elder at Stanford Presbyterian (PCUS) in Kentucky, where he was a member for 45 years. George may have been the first Presbyterian Hopper; his grandfather, Blackgrove Hopper (1759–1831), was a Baptist minister.

Archibald Alexander Barron (1851–1909) was the father of Annis Barron Hopper, wife of Joseph Hopper. He served as an elder at Tirzah and First Associate Reformed Presbyterian in Rock Hill, SC. He was a farmer and owner of Rock Hill Hardware.

The Barron line almost certainly includes more elders and deacons, though I do not have records. According to family legend, the Barrons have been Presbyterian since the beginning in 1560.

Joe B. Hopper describes a Christmas celebration for Korean orphans thrown by missionaries Read More

In April 1972, my dad, a senior at King College, spent a weekend in Montreat, North Carolina. After worshipping at Montreat Presbyterian, Mrs. Ruth Bell Graham–who was a member at MPC–invited dad to Billy and Ruth’s house on Mississippi Road for lunch. In a letter to his parents (who were serving as missionaries in Korea), dad recounts watching the Apollo 16 launch with the Graham’s after lunch:

“Mrs Graham invited (my 2 friends) and me up for lunch. It was the first time I had been up (to the Graham house), and it was quite interesting. Dr. Graham was there and we watched the space shot go off during lunch.

He said that NBC has asked him to narrate the shot with John Chancellor but he had turned them down. It was very interesting talking to him. He really does know the Bible inside out. I got away a little later than planned….

My dad David Hopper, his brother Barron Hopper, his sisters Alice Dokter and Margaret Faircloth grew up in Jeonju, South Korea where their parents were missionaries with the southern presbyterian church (PCUS). On January 5, 2023, I got them all in a room together to share memories of their childhood.

You can listen to the four parts of the interview below.

You can also search for “Ulster Worldly” in your podcast app of choice or subscribe to the feed directly.

Here are links to some things mentioned in the interview:

My friend Matthew Ezzell and I taught a Sunday school class on American Presbyterian History at Shiloh Presbyterian Church.

Here was the overview we wrote for the course:

This class provides an understanding of the historical foundations of modern presbyterianism in America. We cover the breadth of the streams contributing to the presbyterian churches and denominations of our country. In the course, we learn about the controversies and conflicts and also spread of the gospel and the propagation churches throughout the United States. We specially emphasize the origin and development of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church and the establishment of presbyterianism in central North Carolina.

Here are the lessons I taught:

Here is the audio of the class:

Letter from Billy Graham on the occasion of the death of Joe B. Hopper Read More

The Orthodox Presbyterian Church's first tumultuous decade (1936-1946), including internal conflicts over fundamentalism, Machen's death, and the 1937 split that formed the Bible Presbyterian Church. Read More