Pyongyang Years

My grandfather was born in southern Korea where his father was a missionary. As with many missionary children in east Asia—including Ruth Bell Graham—he attended Pyongyang Foreign School, which ran from 1900 to 1940. In his memoir, my grandfather tells about the “Pyeng-yang years” from 1934 to 1938. What follows is the full version of that chapter from my grandfather’s manuscript.1

Missionary children growing up in Korea anticipated “going to PYFS” with anticipation and excitement. After the elementary school years with almost no American playmates and very little activities outside the home and immediate family, we could look forward to “Pyeng-yang Foreign School” where there would be many class-mates, different teachers, and a whole new way of life. Of course there was also speculation as to what dormitory life would be like, how we would get along with a strange room-mate or two, and how a long separation from the protection and guidance of parents could be endured. From the viewpoint of a parent now, more than 50 years later, I realize that these questions were of far greater concern to my own parents than they were to a 13 year old boy like myself.

This traumatic transition was made far easier because we children and our parents had known for years that it was coming, had often talked of it, and were thoroughly prepared to accept it. Because we had lived in Pyeng-yang for some months in the fall of 1931 while Father was teaching at the Presbyterian Seminary and I had been in the fifth grade, I had some general idea of what to expect at PYFS. Academically, mother had done everything possible (especially in mathematics and English) to fit us for the curriculum in Pyeng-yang. She even ordered a Latin text-book and taught me my “amo, amas, amat” in advance so I would have a head start in that subject. We were instructed how to take care of our clothes, how to keep our room neat and clean, what to do if we got sick, and seemingly endless other matters. Mother had ordered from America or had made locally all the clothes I would need and had gathered sheets and blankets and towels. My laundry number (I think it was No. 17) had been sewn with care on every item and my trunk and suitcase were packed with great care.

While the payment of fees to the school were cared for by my parents, a system was worked out for my “spending money.” From the first, I was not given any specified amount as an allowance, but a sum of money to use as needed without any fixed limits. We students could deposit our money in the school office, where we were issued pass-books and little check-books to withdraw funds just like dealing with a bank… good training for all of us. The only condition my parents made was that I periodically send home a list of how the money was used… and for many years even nickels and dimes spent were duly recorded and reported once a month. I cannot recall a single time when such expenditures were questioned or rebuked in any way. Placing this trust in me was an excellent way to make me to act responsibly in the use of what was then their money and is now mine. Possibly this is the reason why during our marriage of 45 years (as of 1990) Dot and I have never lived on a fixed budget of so much for food, so much for clothes, etc. but have tried to use our resources wisely as needed… and we have never been in debt!

Travel to Pyeng-yang involved an 18 hour train trip. Pyeng-yang is the largest city in the northern part of Korea, and is currently (1991) the capital of communist North Korea. As I recall, my mother accompanied me on the first trip and we stopped long enough in Seoul enroute for me to have some dental work done. The trip from Mokpo to Seoul was approximately 12 hours and from Seoul to Pyeng-yang another 6 hours. This was such a long trip that during my years in school I never went home except at Christmas and summer vacation time. One night on the train was necessary, and we always rode in the “third class sleepers.” Three sleeping bunks were stacked in a tier, one above the other. Two of these “triple deckers” faced each other in sections along one side of the aisle like ordinary train seats, and on the other side of the aisle (which was off-center) similar bunks were situated lengthwise of the coach. The bunks were just like ordinary train seats except about 6 feet long. All this was calculated for cramped discomfort with maximum togetherness in minimum space. The only “pullman” serving our mission area left Mokpo in the evening and reached Seoul in midmorning the next day.

Missionary children going to Pyeng-yang from Kwangju had to ride a connecting train to “Sho-ter-ri” (now Song-jung-ni), and those from Soonchun, Chonju, and Kunsan rode other trains to “Ree-ree” (now Iri) to join our train. There were no “sleepers” on their trains, but their “day” coaches were attached to our train from Mokpo. Since it was not permitted by the railway system for them to buy tickets for sleeper reservations in their own cities, and all the spaces would be taken up by other passengers when they reached these connecting points, it became the practice for them to write or telegraph asking us to buy advance reservations for them in Mokpo. Often I would be holding quite a large bundle of sleeper tickets when we met our friends at these points. Imagine the excitement when during in the night, perhaps at ten o’clock in Sho-ter-i and at mid-night in Ree-ree, large groups of American high school children moved themselves and their baggage to our sleeper from coaches which had just been hooked to our train. There were loud greetings with friends they had not seen for a while, as they settled themselves on their bunks. I am sure the other passengers were vastly entertained and perhaps displeased at all the disturbance created by these noisy foreign students, especially since it was late at night before the whole crowd quit talking and went to sleep.

Among other warnings given by our parents as we left home were orders to beware of “detectives.” Korea was now oppressively ruled by her Japanese imperialist conquerors who were in the process of making military moves into Manchuria and North China. Missionaries were regarded with suspicion by the authorities, and all of us Americans were regarded as spies. Possibly they were already planning war with the United States and it was clear that they had embarked on a policy aimed at control of all of East Asia. The Japanese were deeply afraid lest any report that smacked of criticism of their regime be sent abroad, and of course they were always on the alert lest we say or do anything to encourage antiJapanese activities among the Koreans. Our mail was routinely censored and Japanese “detectives” were forever pestering missionaries, coming to our homes, asking all kinds of leading (or absurd) questions, and in general making a nuisance of themselves by attempting to trap us into saying something for which we could be accused.

Missionary children were not exempt from this treatment and we soon learned that wherever we went, even on the train going to school, we were under the watchful eye of detectives. We very soon learned to identify our particular personal sleuth among the other passengers because he would at once try to engage us in conversation with all kinds of questions such as, “What do you think of the Japanese government policies?” or, “Why are you Americans here?” We were trained either to pretend we did not understand, or to say we didn’t know, or to make some other stupid remark. Some detectives liked to practice their English on us, in which case we kids often set them up with all kinds of ridiculous expressions about which we would laugh hilariously later on, mimicking the comical accent of our tormentors. One advantage in all this was that our parents always knew that such a “guardian angel” would guarantee our safe arrival at our destination. We could not have stepped off the train at any stop, or missed a connection, or blundered into any kind of trouble without our private eye watching and reporting our whereabouts. There was a rather long wait between trains in Seoul, and some of the students would go into town briefly, but there was never any danger of them getting lost or failing to keep their travel schedule.

When we crossed the great iron bridge over the Tai-dong River we knew we had arrived in Pyeng-yang, the oldest city in Korea. It was the traditional capital established by Tan-goon, the legendary founder of Korea (2332 B.C.) and boasted an authentic history from the time of King Keui-ja (1122 B.C.) It was rich in the history of various dynasties and rulers, and there were innumerable ancient monuments, gates, pavilions, and temples. Immediately behind our school was a part of what was said to be the wall of Keui-ja and a short distance away an old gate erected a thousand years before… said to be the oldest structure in Korea.

Pyeng-yang was also noted as the point where Protestantism entered Korea when the Rev. Robert J. Thomas was martyred in 1866. This missionary to China had sailed up the Tai-dong river on the “General Sherman” which was attempting to open up Korea to diplomatic relations and commerce. It ran aground opposite the city, and in an incident of which we Americans cannot be proud, the crew antagonized the local populace so that their boat was set afire, and the crew and passengers were killed. Thomas gave out copies of Chinese Scriptures as he died, and through them the first converts to Christ were won. When we were in Pyeng-yang there was an old gate beside the river. I remember that the year Father taught in the seminary he took us there and found the caretaker who unlocked the upper part of the structure for us. We climbed to where we saw the great iron anchor chain of the “General Sherman” locked around one of the columns. Thus in all kinds of ways our education was in an environment of ancient history and culture which not many students are privileged to enjoy.

Our school was located in a suburban area and was a part of the greatest missionary complex in the whole world at that time, so we were told. There was a huge concentration of “Northern” Presbyterian and Methodist missionaries living within walking distance of the school. We were constantly exposed to this unique missionary community of outstanding men and women who laid the foundations of the Korean Church of today. Because of the cooperative work of the several Presbyterian Missions, there were also two “Southern” Presbyterian families. Dr. and Mrs. W. D. Reynolds lived here where he was a professor in the one and only Presbyterian Theological Seminary in the nation. Mr. and Mrs. William Parker lived here where he taught in the Union Christian College (Soong-sil College). There were also extensive medical, Bible institute, and high-school level mission institutions in the area, and all of them were a part of a comprehensive Christian movement. The missionaries took a keen interest in the students at PYFS, opening to us their homes, participating in school activities of every kind, and doing their best to be our parents away from home. Even in the midst of their busy lives, they saw as part of their calling a responsibility for helping to influence and mold our lives.

Arrival at school was always a great time for greeting old friends and making new ones. Students came from every part of Korea except Seoul where there was a large foreign school for local students but no boarding department. There were also quite a few from China, Manchuria, and Japan. These represented many denominations (although mostly Presbyterian and Methodist), and several countries besides the United States, such as Australia and Canada. The principal was Mr. Ralph O. Reiner (known by his affectionate students as “Roar”) of the “Northern” Presbyterian mission. Teachers came from all parts of the U.S. representing various denominations. The school had grown from a small elementary school begun in 1899 to include a full fledged high school of over a hundred students. The academic building provided class-rooms, science laboratory, offices, chapel, and library. There was, of course, a boys’ dormitory and a girls’ dormitory. Kitchen and dining facilities for all of us were in the latter. Tennis courts were opposite these dormitories. While I was there a gymnasium was built, adjacent to the athletic field.

Upon arrival, the immediate concern was: “Which room will I get in the dormitory, and who will be my room-mate?” My first room-mate was Norman Larsen, one of the few students whose parents were not missionaries. They came from Norway, and his father worked with a gold-mining company in the extreme northern part of Korea. We got along amicably but for some reason never developed a strong friendship. We shared a room with two steel cots, a couple of small desks and chairs and a closet. There was a small toilet for the boys on our floor and showers were in the basement. We were expected to take complete care of our rooms, making beds, keeping things straight, and cleaning. Every Saturday morning we underwent “inspection” by the dormitory matron, Miss Lois Blair. She was the daughter of missionaries and though pint sized could keep under discipline a dormitory full of boys by exercising full authority and yet remaining a good friend of all of us.

On Sunday morning we were lined up in the “parlor” for her to inspect fingernails, shoe shines, haircuts, and proper attire for going to Sunday School. By late Sunday afternoon she checked to make sure each of us had written a letter home… under threat of no desert at supper if we failed. This developed a habit which I maintained as long as my parents lived, although when I became a preacher in charge of leading worship services the letter sometimes had to be written the next day. Nevertheless all this discipline was excellent training and I have never regretted any of it.

Our meals were in the dining hall on the first floor of the girls’ dormitory. About eighty boarding students ate together along with most of the faculty who also lived in the dormitories. Every week a new seating arrangement was posted on the bulletin board. At each table there were approximately an even number of boys and girls and usually one teacher. Of course there was either great satisfaction or groaning depending upon whether it was a “good” table or not (meaning our best friends or those we loathed). We stood for the blessing and then sat down. Boys and girls were seated alternately and the boys were expected to pull out the chair and seat the girl next to them.

Food was always good, wholesome, and plentiful… although it would not have been normal had we not complained at times. Once a week the breakfast cereal was “Ladybugs and Beetles.” It was perhaps the most popular, and consisted of boiled beans of two kinds, size, and colors. It was served in large Korean rice bowls and sprinkled with plenty of brown sugar and milk. From a distance of 50 years this dish sounds most un-appetizing but in those days many of us boys could consume more than one bowl. Every Thursday night we had an oriental meal. There were several menus served in turn: Sin-sul-lo (Korean), Man-doos (Chinese), Egg-foo-yong (Chinese), Su-ki-yak-ki (Japanese) and sometimes there was Pool-koh-gi (also Korean)… and always mountains of rice. We ate with chopsticks and thoroughly enjoyed such meals. Otherwise, our meals were fairly conventional American style, although they were largely dependent for ingredients upon what was available in the Korean markets.

Every week-day night we were required to attend study hall at the school for a couple of hours. This was a supervised period either in class-rooms or in the library which was well stocked with everything we needed. When we became seniors we were allowed to study in our own dormitory rooms and to stay up a half hour longer after the usual nine-thirty “bed-time” for other students… provided our grades were above a certain average. I had no trouble with this condition, and was even exempt from most of the final exams that year because of good grades. This room privilege did allow opportunity for some “un-approved” activities.

For instance, we discovered that on the one night each week when ice-cream was our desert for supper, the remnants left in the hand-turned ice-cream freezers in the kitchen were feasted upon by the teachers after we went to bed. This was deemed a grossly unfair infringement on our rights. It happened that we had a pair of twins in our class (Gordon and Helen Kiehn from China) and they shared the use of a portable typewriter. At the appropriate time in the evening, when other students and teachers were at the study hall, Gordon would go to the kitchen in the girls’ dorm and bring back a large bowl of ice-cream which we would consume with great gusto. If challenged as to why he was making a nocturnal visit to the girls’ dorm, he would reply: “I’ve come over to get the typewriter from Helen, " which was understandable and permitted. This went on for quite a while until the faculty appeared to be getting suspicions and we ceased our criminal activity before getting caught!

Tommy Brown was an avid photographer and had flash equipment using magnesium powder set off by an electric spark from a small battery. One night he was playing with this, and devised a way to explode some by using part of a typewriter ribbon can tied below an electric light bulb with the glass broken off. A short piece of lead fuse wire between the two exposed “poles” sparked the powder when contraption was screwed into a light socked and the wall switch was snapped on. It worked so well that he fastened it into the overhead light of a small private bathroom used only by the teacher on our hall. When Mr. Crowder came in and prepared for bed, he stepped into that little room, snapped on the switch, and there was a tremendous flash. The glass shade broke around his head, and the whole place was filled with a cloud of white smoke. He probably knew perfectly well who was responsible, but never said a word to the culprit, now the Rev. Dr. G. Thompson Brown!

A short distance away was the school building where we spent most of our waking hours. The curriculum was the standard one which prepared us to enter college in the United States. Perhaps we did not have the variety of options provided to American students in those days, and certainly not what they can choose today. For instance, I took Latin and mathematics all four years and Miss Blair (our dormitory matron) was my teacher. The only science course I took was chemistry under Mr. Whang, a Korean who was also athletic director. He spoke English fairly well, but I fear we sometimes made fun of his quaint expressions and embarrassed him. Years later he was for a brief time a very high official when Syeng-man Rhee was president of Korea, and then became quite wealthy as a business man, heading a firm with tuna fishing boats in distant waters and a canning factory in Korea. Our music teacher was Mr. Dwight Malsbury who had started me learning the violin when we were in Pyeng-yang when I was in the fifth grade. He was the music professor at the Union Christian College but gave all kinds of instrument lessons and led the band at PYFS. He was a brilliant pianist and also faithfully did street preaching on Sunday afternoons. After World War II he lived in Pusan as a missionary of the Independent Presbyterian Mission, and devoted himself full-time to evangelistic work. I felt that in so doing he neglected his greatest gift as a musician, although he did keep up some of it.

There was great excitement over one “scandal” in the faculty. A young man was teaching in the elementary school and became a good friend of a music teacher considerably older than he. One March day, a Japanese detective came to the principle’s office asking about “Mrs.” Reck. Mr. Reiner replied that there was no “Mrs.” Reck in the school, but that there was a “Mr.” Reck. “Oh no!” insisted the detective, there is a “Mrs. Reck.” Our records show that your “Mr.” Reck married this lady in Hong Kong during the Christmas season.” Mr. Reiner was astounded and as furious as he could be! It was against the school regulations for faculty members to marry each other. He fired them both without hesitation and they left that day, sending a shock wave through the school and the whole community. The couple went to the gold mines in the northern part of the county where Mr. Reck found work at once. Some time later, while I was still at PYFS word came that he had been killed in an ore-crushing machine. The school authorities had the grace to allow his body to be returned for burial in Pyeng-yang, and we all attended the funeral held in the school gymnasium. I never did learn how, in the days before there was any air travel, this couple managed to get all the way to Hong Kong and back by boat during the short Christmas vacation.

Perhaps the teacher who influenced us the most was Dr. Donald G. Miller.2 His first year in Pyeng-yang was during my sophomore year which I spent in America when our family was on furlough. But he was there in my junior year when I studied English and Bible under him. Although under a three year contract, he was so anxious to return and marry the lady to whom he was engaged that he stayed only two years. He was a graduate of Biblical Seminary in New York and an excellent Bible teacher using the “inductive” methods taught in that institution. Because classes were small, some were combined, as was the case for junior and senior Bible. Ruth Bell (now Mrs. Billy Graham) from China was a senior and in the same Bible class with us. Dr. Miller was then a Free Methodist, but Ruth was a dyed-in-the wool Presbyterian, and the two of them had great debates about predestination. She must have won the battle, because not many years later after returning to the States he became a Presbyterian. When I was in my second year at seminary (1943) it was with great enthusiasm that I could welcome Dr. Miller to Richmond as my English Bible professor and I was privileged to be his student for two more years.

Dr. Miller was not only influential in the class-room but in other ways too, especially as our scout master. Most of the boys in the school were in the Boy Scout troop and he took his duties seriously, faithfully holding the meetings, helping us with our advancement, and taking us on hikes and camping trips. I reached the rank of “Star” Scout and at graduation exercises received the Bob Erwin Award as a “distinguished” scout. (Bob came from China and his parents set up this award in his memory after he was killed one night on the railway tracks behind our dormitory under rather mysterious circumstances. Some of us always felt that he took his own life.) In Dr Miller’s first year at PYFS he somehow managed to acquire a place out in the woods not too far away where the troop built a small cabin and we could spend the night occasionally. I still remember how on several occasions he cooked oatmeal for breakfast in a five-gallon oil can, and then afterwards scrubbed out that messy can with his own hands.

Once Dr. Miller took us for a week-end to a distant mountain fortress… a great walled area constructed by some Korean war-lord hundreds of years ago. Each spring it was traditional for the school to allow a day or so holiday for the scout troop to go camping at “Misty Point” which was a bend in a river where we could swim safely. There was a Methodist missionary in Pyeng-yang, Dr. William Shaw, who had served as a chaplain in World War I and loved to be with our Boy Scout troop although he did not have time to serve as scout master. Dr. Miller would invite him to join in some of these outings to lead our devotional services which were always most inspirational and challenging to boys.

Every morning at the school we had a chapel service, attended by all the students and faculty. It was usually led by one of the teachers, and when the principal, Mr. Reiner, rose to make announcements we all trembled, not knowing how or where he was going to lower the boom on us for some real or imagined misdemeanor. There were also outside speakers. I recall that once Bishop Arthur Moore (missionary bishop of the Methodist Church) spoke. Another time there was a little bald-headed man who talked about the healing of Naaman the leper. Every time he mentioned Naaman bathing in the River Jordan he ducked all seven times behind the pulpit leaving only his bald pate visible much to our amusement. Students also took turns leading the service, and I recall doing so at least once. Of course we sang all the hymns, both the great classical numbers and the popular “Gospel” type.

Every Sunday morning we trooped over to the Presbyterian Seminary for Sunday School, usually taught by local missionaries rather than our school teachers who were with us during the week-days. After Sunday School it was customary for all children of “Southern” Presbyterian missionaries to walk over to the home of Dr. and Mrs. W. D. Reynolds. He was usually out preaching somewhere, but “Grandma” Reynolds always welcomed us. She knew all of our parents and families and took personal interest in each of us. The only refreshments she provided were roasted peanuts of which there seemed to be an unlimited supply.

Sunday afternoon we again went to the seminary chapel for the worship service in English attended by the entire missionary community, making quite a large congregation. Our preachers were usually local missionaries but sometimes guests from abroad such a Dr. Robert E. Speer or Bishop Arthur Moore. Occasionally Dr. Reynolds, professor of systematic theology, took his turn preaching. While absolutely orthodox and Biblical in his messages he tended to be rather dry and long-winded. When he prayed he would forget all about his surroundings while talking endlessly to the Lord and would never have come to the “Amen” if “Grand-ma” had not been sitting in the front pew. When she thought that the “conversation” had gone on long enough, she would loudly clear her throat… and the prayer would end abruptly!

On Sunday evenings we had “Christian Endeavor,” and of course all the students were members and expected to attend the meetings. We were divided into groups which usually met in the homes of missionaries in the community. Here again we became friends with these great saints, heard tales of their remarkable experiences, and were exposed to their fine influence. It was also a superb way in which to learn how to be at ease leading in worship, praying in public, and so on. Occasionally I went to Korean Church services. The largest church near our school had so many members that they had a service for the women in the morning and one for the men early in the afternoon. I recall attending one service when about 100 men were baptized. It was necessary to have two ministers going along two lines performing the sacrament at the same time.

Not only in high school, but for the rest of my years in college and seminary, I was more of a student and book-worm than participant in extra-curricula activities. We had a full athletic program (soccer, basketball, ice-hockey, tennis) and I would faithfully take part during the physical education class times, but not much more than that. The only exception was tennis which I enjoyed and played whenever possible but I was never a champion. I was in the school choir, and for a while in the band. There were all kinds of entertainments, parties, athletic contests, and plays. I think I was only in one play and on the stage a moment or two with a one-line or two remark, but I never enjoyed that sort of thing at all.

Dating was allowed but strictly controlled and chaperoned, usually by one or more of our teachers. It was customary for the boys to take the girls to the various school functions, but there was very little of this off campus. In warmer seasons, our class occasionally rented a boat for a ride and picnic up the Tai-dong river, sailing past some of the beautiful hills and colorful pavilions commemorating ancient historical events. The boat had a flat bottom where we could sit, and was propelled by a Korean with a long sculling oar which he twisted from side to side over the stern. Only rarely was there an American movie worth seeing, but occasionally a large group of us would go together with some faculty member to see one of the classics of that era such as “Rose Marie.” With all these activities we never felt deprived of a full and happy life and formed friendships which last until this day. Because we were such a small self-contained community, with each other in the dining room, classroom, athletic field, and other times in between, we never really lacked satisfactory social life.

Because the winters are so cold in Pyeng-yang we did a lot of ice-skating for three months or more. On my first Thanksgiving Day there, we had a holiday. A small river behind our dormitory was frozen solid and I spent almost the whole day learning to skate. The school had a regulation size hockey rink which was flooded regularly for our use in physical education class, for ice-hockey, and for recreation. We had a good hockey team largely made up of boys whose families lived in these cold regions and who had skated almost all their lives. The rest of us would often skate after school in the afternoons and all day Saturday. Sometimes on Saturday night the whole school spent the evening in a skating party. There would be a big fire beside the rink, apples and chestnuts to roast, and everyone had a great good time. Once or twice we went at night across the city down to the Tae-dong River which was solidly frozen. An enormous area had been cleared of snow and a skating oval prepared for the people of the city, a great many of whom enjoyed this sport. Fires were built out on the ice for light, heat, and to roast food. We never seemed to mind the bitter cold temperatures which were often below zero.

During these years we were not unmindful of momentous events taking place all around us. The main double track railroad connecting Japan and China through Korea ran right behind our dormitory, separated only by a low hill which may have been an ancient city wall. This was the main route for transporting invading Japanese troops and military equipment moving into Manchuria and China. Long troop trains and cars loaded with tanks, artillery, trucks, and so on were continually passing along this route. We were forbidden by the suspicious Japanese authorities to climb the hill and watch for fear that we spies might report to our own respective governments what was going on (but we did sneak a look now and then!) A major Japanese airfield was just across the Tae-dong River from the city. In those days planes could not easily fly the long distances from Japan to China but Pyeng-yang was a forward base and close enough for their purposes. We could watch constant dog-fights as their single engine fighters practiced maneuvers overhead. Squadrons of multi-engined bombers would also thunder over-head. Little did we realize that all this would eventually lead to a great world war!

At this point in the manuscript, Joe stops to describe the trip around the world that his family took during their 1935 furlough.

Now we were back in Korea and I began my junior year in High School at Pyeng-yang. That year I roomed with Hamilton (Ham) Talbot (a senior from China) and Walter Levie (a classmate and the son of our mission dentist in Kwangju.) We were great friends. Because seniors could choose their roommates, Walter and I agreed to be together our last year. But the year had hardly started when the matron asked me to room with a new boy from China and put Walter elsewhere, much to our displeasure.

A few days later George Thompson Brown, known as “Tommy,” arrived. His parents were Dr. and Mrs. Frank A. Brown, missionaries to China, and was born in Ruling. He grew up in Suchowfu and had attended Shanghai American School until then. But because the Japanese military action in China made it impossible for him to get to Shanghai, he had taken the long train trip via Manchuria to our school. When Christmas vacation time came, he could not make the trip home so I invited him to come to Mokpo with me and my sister Mardia who was a year behind us in school. Later he and I roomed together for four years at Davidson College, and he married my sister Mardia in Gaither Chapel in Montreat in 1943. At the time he was a lieutenant in the army, and after the war he attended Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, was a pastor in Gastonia for several years, and came to Korea as a fellow missionary.

Superior teachers, distinguished missionaries, exposure to other cultures, and the advantages of travel were all parts of the exceptionally wonderful guidance and training we had during these formative years. Since almost all the students came from homes where both parents were professionally trained as ministers, doctors, nurses, or professors (many with advanced degrees) it is not surprising that the level of education at PYFS was higher than average and that almost all the graduates went on to college and graduate schools. If my memory is correct, a survey at the time the school was closed just before the beginning of World War II, showed that there was a higher percentage of the alumni elected to Phi Beta Kappa than that of any high school in the United States. Naturally the number entering Christian work was also very high. Four members of my class of 1938 became career missionaries of the Presbyterian Church: Virginia Montgomery (Mrs. Don McCall, in Japan and Taiwan), Catherine McLauchlin (Mrs. Lyle Peterson, in Japan), Tommy Brown and I (in Korea). Several other members of our class belonging to other denominations were also in similar work.

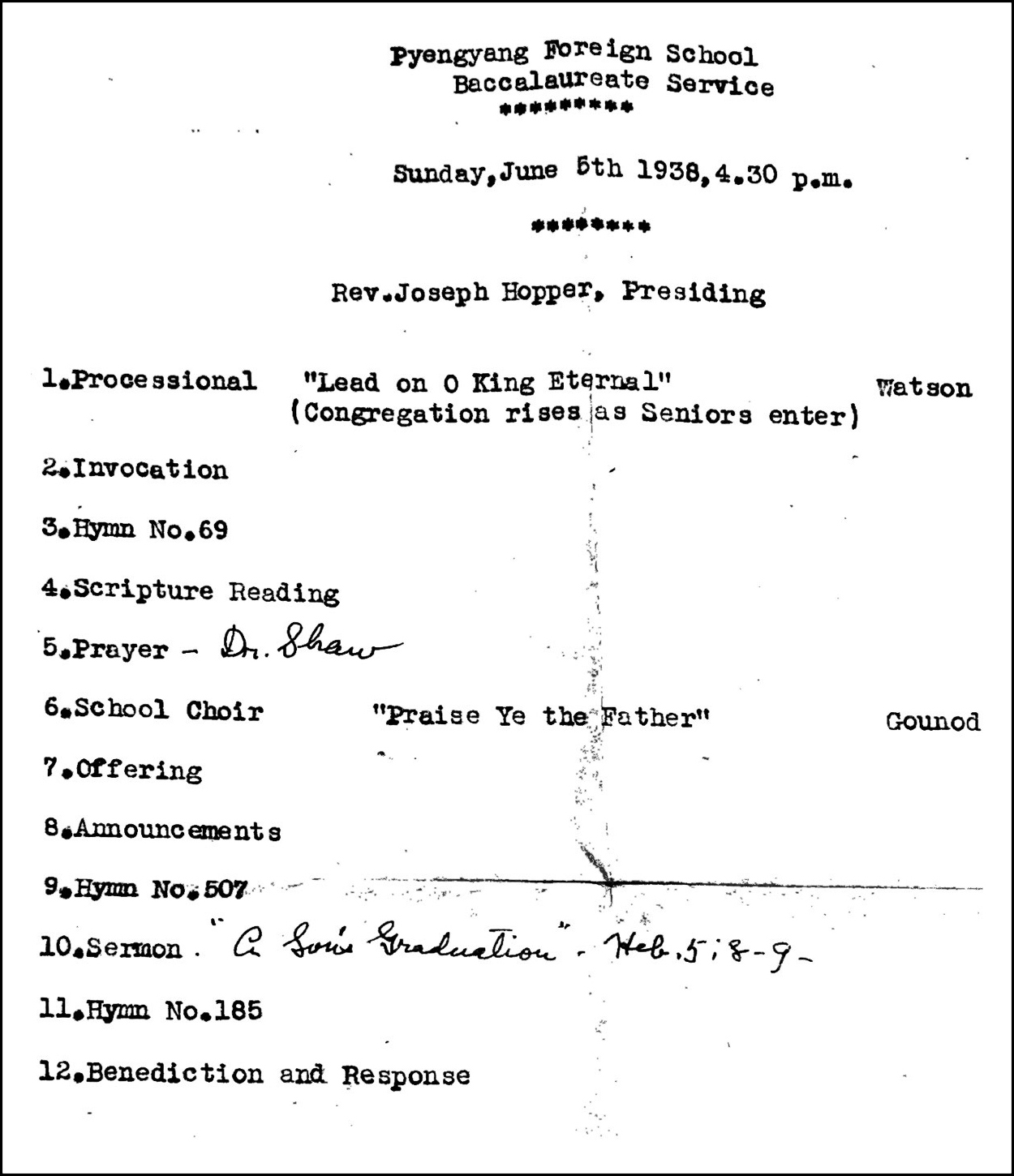

Commencement exercises were (I believe) on June 7, 1938. Father preached the baccalaureate sermon on the subject “A Son’s Graduation” based on Heb. 5:8-9. Virginia Montgomery was the class salutatorian, and I was valedictorian. Both of us had to make short speeches. Mine had been written, reviewed by the principal, and memorized. Right in the middle of my “oration” a large formation of Japanese bombing planes flew low over head. The roar was so deafening I had to stop speaking… and nearly lost my place as a result! Somehow I don’t remember too much about it, probably because I was so relieved when it was over.

My sister Mardia graduated from PYFS the following year. My brother George’s education there was cut short in the fall of 1940 when almost all of the missionaries were forced to evacuate… about a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. During the first winter of the Korean War a few missionaries were able to enter Pyeng-yang briefly. They found that most of the mission property, including our school, had become the headquarters of the communist regime of dictator Kim Il-seung, and that is very likely still the case today. But the impact of that school on scores of missionary children, and subsequently through them upon the work of our Lord in many lands around the world can never be measured!

-

The Hoppers had lived in Pyengyang for a semester when my grandfather was in 5th grade when his father, Joseph Hopper, was asked to teach at Union Theological Seminary. ↩︎

-

Donald Miller would later become the president of Pittsburg Theological Seminary. —Tim Hopper ↩︎