Barrons of Scotland

The great Scottish reformer John Knox was born in 1514, three years before Martin Luther would publish his Ninety Five Theses, in Haddington. After being ordained a Roman Catholic priest, he embraced the reforms of protestantism and became a minister in 1546.

In 1547, a French fleet besieged St. Andrews Castle where Knox and other protestants resided. On July 31, 1547, the castle was captured by the French. Knox and others were forced to become galley slaves on French ships.

Knox would eventually escaped enslavement and, in 1556, took refuge in the Swiss town of Geneva where he pastored a small church of English-speaking protestant refugees. In Geneva, Knox fellowshipped with the French reformer John Calvin, who was just a few years older than Knox.

The reformation in Scotland continued in Knox’s absence. In March of 1557, five Scottish nobles wrote to Knox asking him to return to Scotland.

In The Life of John Knox, Thomas M’Crie writes,

James Syme, who had been his host, at Edinburg, and James Barron, arrived at Geneva, with a letter from the earl of Glencairn, the lords Lorn, Erskine, and James Stewart, informing him, that those who had professed the Reformed doctrine, remained steadfast; that his adversaries were daily lose credit to the nation, and that those who possessed the supreme authority, although they had not yet declared themselves friendly, still refrained from persecution; and inviting him in their own name, and in that of their brethren, to return to Scotland, where he would find them all ready to receive him, and to spend their lives and fortunes in advancing the cause which they had espoused.

With the blessing of John Calvin and his congregation, John Knox returned to his homeland in May of 1559.

In August, the Scottish Parliament met to address the issue of religious reform. They commissioned the Six Johns to write a Confession of Faith, and they severed the authority of the Pope over the Scottish churches. Knox and other ministers were given the authority to organize the Scottish reformed church. The Johns then prepared a book of church order called the First Book of Discipline.

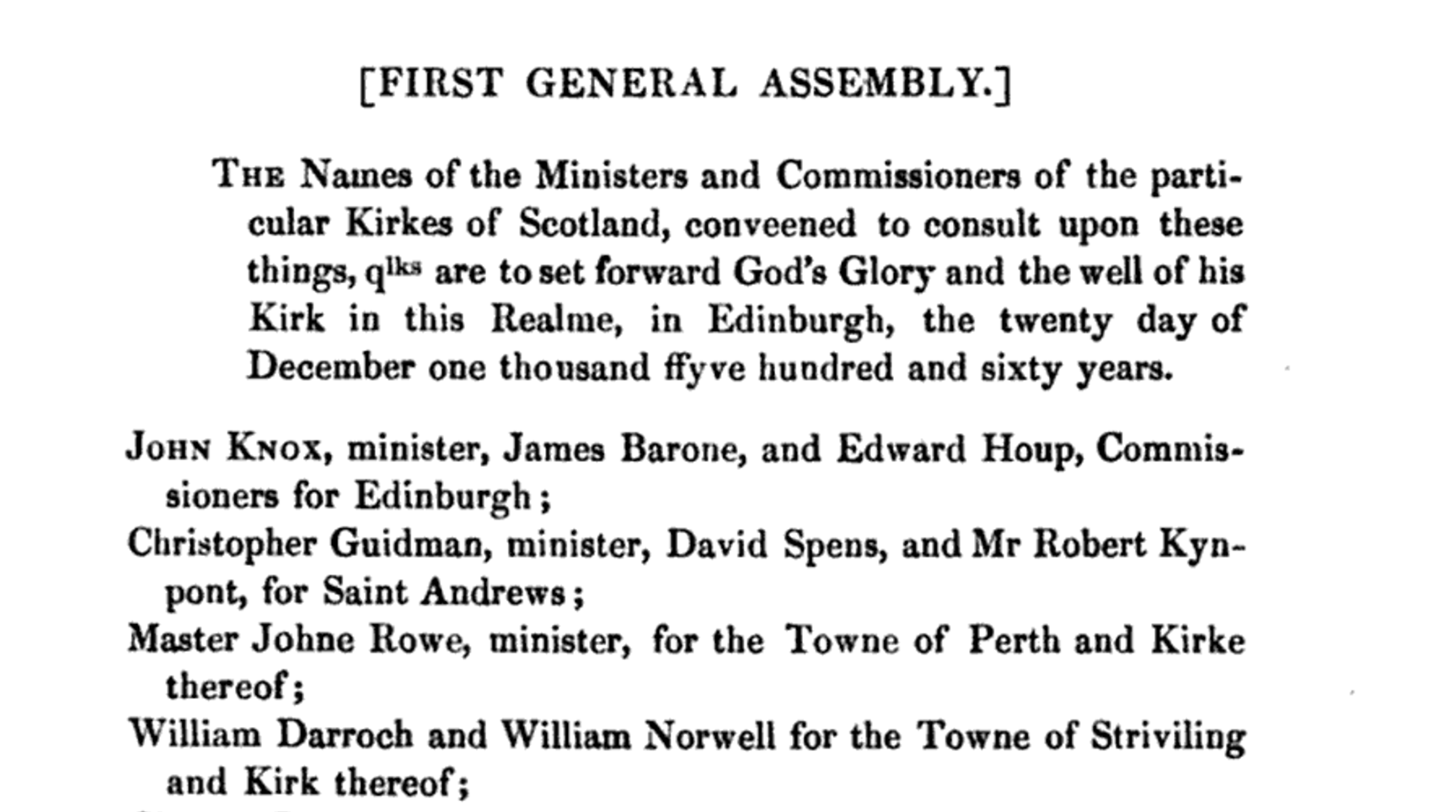

On December 20, 1560, the Church of Scotland convened its first general assembly with forty commissioners from across the nation. Only six of these commissioners were ministers1; the others were lay elders.

Edinburgh was represented by John Knox (minister), James Barron, and Edward Hope.2 This was the same Barron who carried a letter from Scotland requesting Knox return to Scotland. Barron was Dean of the Guild in Scotland, a role which included handling trade disputes and overseeing town buildings. Barron and Hope were lay leaders in the new church; in modern presbyterian terminology, they were ruling elders.

Despite these reforms, religious turmoil continued in England and Scotland. In the 1600s, many Scottish Presbyterians would flee to King James’3 Plantation of Ulster in Northern Ireland.

One of these family was that of William Barron, who, according to family lore, is a direct descendant of James Barron, the colleague of John Knox. In 1734, Archibald Alexander Barron was born to William in Carrickfergus, Ireland. Archibald would immigrate to Pennsylvania in 1769 and would follow the Great Wagon Road to York County, South Carolina. The Barrons of York County would end up members of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church,4 which formed from offshoots of the Church of Scotland.

In the late 1910s, Archibald great-great granddaughter Annis Estelle Barron (1893-1979) traveled to New York City to attend the Bible Teachers’ Training School in preparation to serve the United Presbyterian Mission in Egypt. There she met Joseph Hopper of central Kentucky. Meeting Joseph interrupted Annis’ plans; Joseph and Annis married on December 18, 1919 and, three months later, moved to Mokpo, Korea where they would serve as PCUS missionaries for 34 years. Joseph and Annis’ son Joseph Barron Hopper, my grandfather, would return to Korea with his wife Dot and serve the Lord for 38 years.

History forgets ruling elders. Yet without the faithful service of James Barron, there may have been no one to summon Knox back to Geneva. Without John Knox’s return to Scotland, we may not have the gospel-preaching presbyterian churches that exist around the world today. I thank God for the forgotten faithfulness of my ancestors.

-

John Knox (Edinburgh), Christophere Gudman (St. Andrews), John Row (Perth), David Lindesay (Leith), William Harlaw (St. Cuthberts), and William Christesone (Dundee) ↩︎

-

As in the King James Bible ↩︎

-

Many of the Barrons are buried in the Ebenezer Presbyterian Church Cemetery. ↩︎